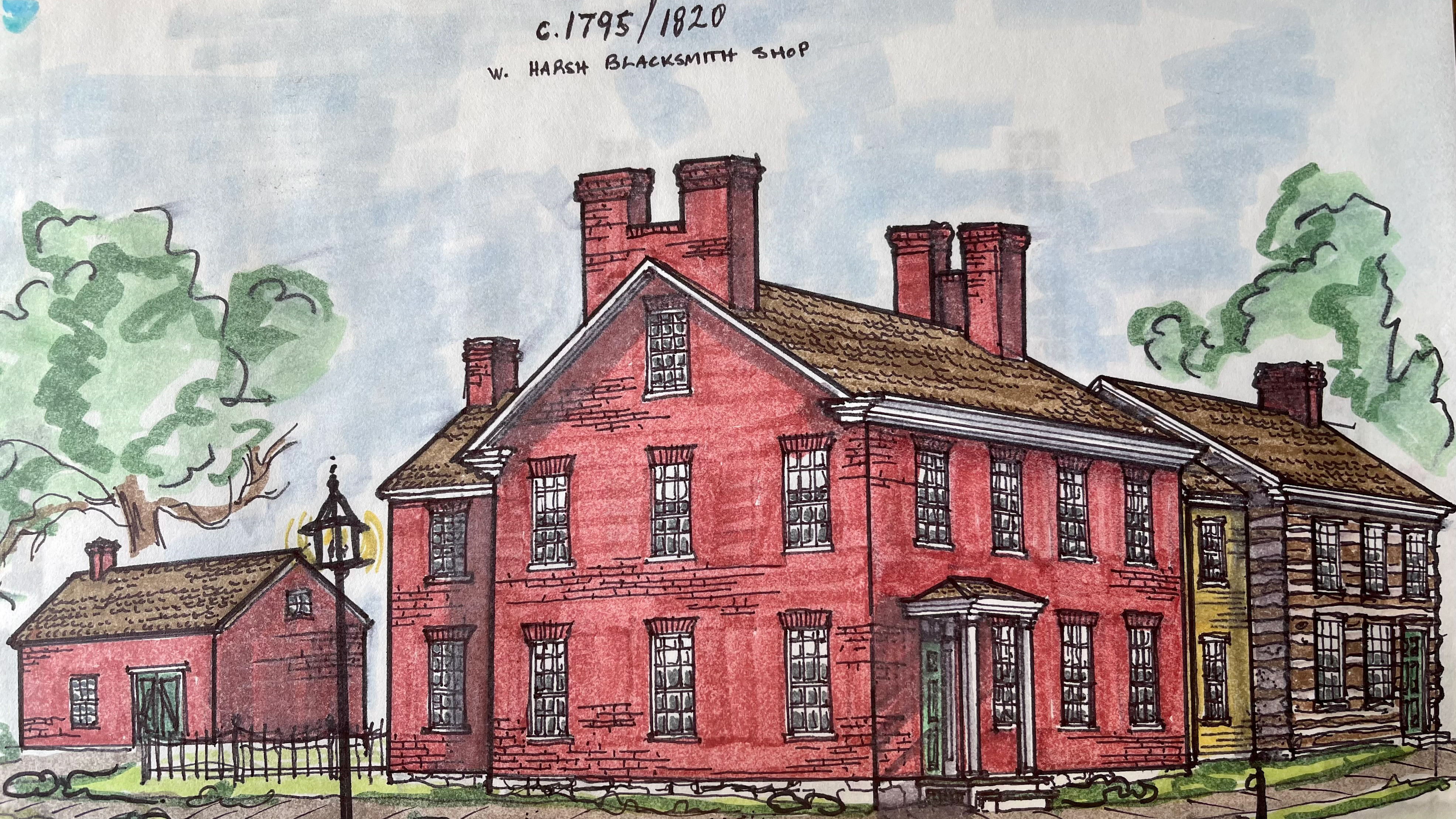

A grand, two-story Federal-style six-bay Flemish bond brick home has stood on the south side of E. Salisbury Street in Williamsport for over two hundred years. It’s not a quiet house; the scale is massive compared to other homes in the town, standing 60 feet wide, 40 feet deep, plus a two-story 20 ft by 17 ft servant’s wing to the rear and a late 19th-century second-floor glass conservatory.

The mansion employs five massive chimneys, four of which are paired at the main block's end walls. Corbeled brick parapets accent the roof-line. A huge cornice runs along the façade with dentil molding nailed in place with original square-cut nails. A jib window, an extremely rare feature for this area of the country, leads from the second hall to the upper gallery of the two-story front porch. Entering the home, you find a grand entry hall with a beautiful Georgian/Federal Style staircase rising continuously for three floors. The ceilings on the first floor are nearly thirteen-feet high with massive crown moldings, and over eleven feet tall on the second. Intricate Federal mantelpieces with hints of Adams styling decorate the ten fireplaces. With these refined details, it is almost inconceivable that this home was built to be a bank.

The grand entry hall with a beautiful Georgian/Federal Style staircase rising continuously for three floors

The Upstairs hallway with a jib window that leads out onto the second-story porch. Jib windows are rare in this area, being found more in southern homes for ventilation.

The original Hagerstown Bank was built in the "banking house" fashion of the early 19th century. Erected along W. Washington Street, this banking house was demolished in 1936.

Before and after George Washington became our first president in 1790, there were only three banks in the United States. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton moved quickly to give the United States a modern financial system and authorized State legislatures to charter corporate banks.

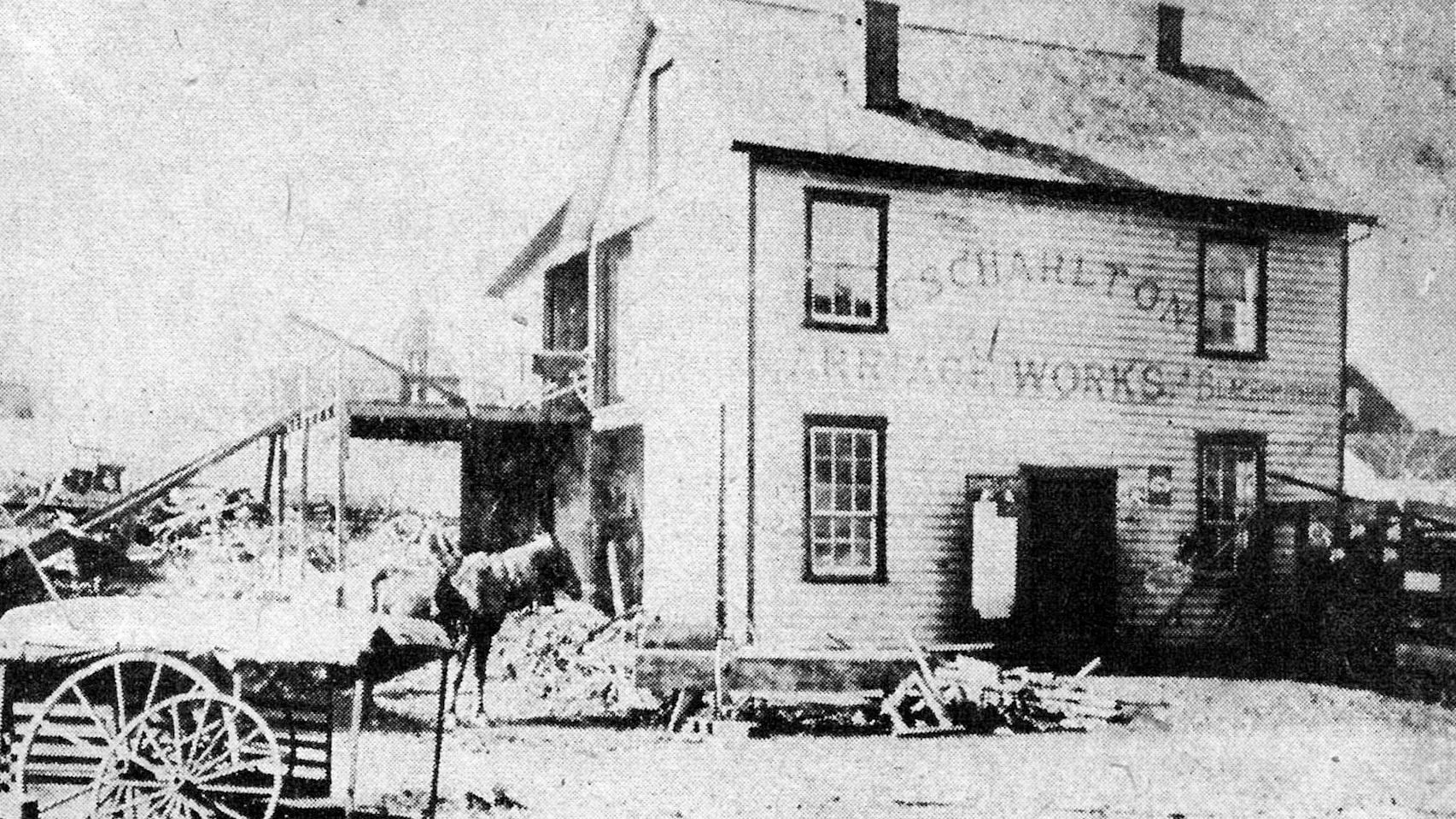

The Maryland charter Conococheague Bank of Williamsport received approval to incorporate from the Maryland Assembly in 1813. A list of the directors of the short-lived Conococheague Bank reads like the who’s-who of local landed gentry: Congressman Samuel Ringgold, owner of the 18,000 acres Conococheague Manor and builder of Fountain Rock (present-day St. James College); John Dall, builder of Dalton, Judge John Buchanan, builder of Woodland, Judge Thomas Buchanan builder of Woburn Manor, General Edward Green Williams, owner of Springfield Farm and most of Williamsport, Samuel Chew, owner of the 5,000 acre Chews Farm south of Downsville, Matthew Van Lear, builder of Mount Tammany, and Michael Findley, owner of Findley’s (Red) Mill). The directors of the Conococheague Bank were likely seeking to imitate the success of Nathaniel Rochester in Hagerstown. Rochester first opened the Hagers-town Bank in 1807, conducting business in the front parlor of his home. In 1814, the corporation built an elegant Greek Revival style banking-house along West Washington Street – incidentally, the same year the Conococheague Bank received its charter. Under the solid management of long-time cashier Eli Beatty, the Hagers-town Bank was incredibly successful, withstanding and prospering through several financial depressions. Rochester left Hagerstown in 1810 for New York State, but the bank he founded remains alive and well today, trading as the Hagerstown Bank and Trust Company. Unfortunately, the Hagers-town bank building was demolished in 1936.

As the young nation and banking institutions developed, banking houses were fashionable in the early 19th century. Typically built along the town’s main streets, banking houses looked more like Greek Revival or Georgian mansions. Very few of these purpose-built structures survived the march of progress; today, only four known surviving examples exist.

Williamsport is exceptionally fortunate to have retained one of these extremely rare buildings. The interiors of banking houses were ample, well-appointed public spaces for financial transactions, private rooms for directors to deliberate loans, and a secure place for cash, notes, and securities. A small attached dwelling was often added for the cashier’s residence to “accommodate a family and answer for banking purposes,” such as in Worcester, Massachusetts. Unquestionably, these banking houses projected an air of opulence designed to reflect the prosperity and security of the financial corporation. The banking-house fashion was soon replaced by more institutional-looking fortresses that became the standard for modern banks.

The library today in the old Williamsport Banking House

The Conococheague Bank operated from 1814 until 1819 in a rented structure on the corner of Conococheague and Potomac Streets while their elegant banking house was being constructed on E. Salisbury Street. Some written histories of Williamsport say Peter Steffey built the house in 1804. Steffey was a local contractor, so it is reasonable he may have been the builder; however, the evidence suggests a build date of 1814. Interestingly, Steffey’s descendants would later purchase the mansion and own it for seventy-five years. Edward Greene Williams and his brothers sold lot #95 on E. Salisbury Street to the Conococheague Bank in 1819; however, it is almost certain that their banking-house was complete or nearly complete when Williams sold the land to the bank. Unfortunately, coinciding with the completion of their new headquarters came a crippling economic depression the young corporation could not withstand.

The stockholders met in their lovely, newly built banking house on December 23, 1819, and resolved to an early dissolution. The Maryland Assembly authorized the bank to liquidate its real estate assets at a public auction one year later.

As the economic depression deepened, the mansion was offered at public auction several times in 1821 and 1822 without success. Opening a corporate bank seems to have been easier than closing one. As late as 1835, there were still unresolved transactions and legal actions arising from the closure of the Conococheague Bank.

According to articles in the Maryland Herald and Hagerstown Weekly Advertiser, on June 6, 1841, the banking-house was leased by the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company for their headquarters after the board of directors voted to move their base from Frederick to Williamsport. The article states the decision as “highly proper, as Williamsport is situated immediately on the banks of the canal and is about midway from the extremities of it.”

The grand house on E. Salisbury Street remained officially unsold until 1846, when William Towson, then president of the defunct bank corporation, sold the property for $1,050 to local lumber dealers Adam Shoop and Doctor Samuel Weisel. The deed specifies lot #95 on E. Salisbury Street, with a two-story brick house and other improvements. Shoop and Weisel were brothers-in-law, Shoop having married Susan Weisel, the doctor’s younger sister. It is unclear which family lived in the house for the next twenty-odd years.

As the residency of either Weisel or Shoop, the Civil War visited Williamsport several times. During the retreat from Gettysburg, Pa, in early July 1863, General Robert E. Lee and his army commandeered the entire town while repairing destroyed bridges at Lemen’s Ferry. Lee marched right down Salisbury Street past the house. Next door, the old brick Church of the Brethren served as a makeshift surgery, and the lawn on the east side of the house a makeshift mortuary.

The arrival of the C&O Canal in the 1830s brought prosperity to the town, and prosperous merchants such as the Cushwa’s, Byron’s, Embry’s, and Steffey’s built some of the finest homes in the town. But Caroline Steffey wanted the bank mansion, and sometime in the early 1870s, Doctor Weisel and Adam Shoop finally agreed to sell it to her for $1,075. When Doctor Weisel died in 1872, followed by Shopp in 1873, the Steffeys had not yet paid for the house. Two years later, the Shoop and Weisel widows received authority from the Orphan’s Court to consummate the sale. With the balance settled, a deed was recorded in July 1876, naming William Steffey’s wife, Caroline, as the new owner.

The second-floor hallway

The front parlor off the grand entry hall

Peter Steffey (1782-1863), the believed builder of the Conococheague Bank, moved from Pennsylvania to Williamsport in the late 18th century, marrying Catherine Tritle (1788-1844) in Hagerstown in 1804. A prolific family, the marriage produced an estimated seventeen children. His second child, William Steffey (1807-1891), was born in 1807 at Williamsport. William Steffey married twice; his first marriage produced five children, including Edward Steffey (1836-1899), one of the founders of Steffey-Findley in 1873 – a business that still thrives today in Hagerstown. After Catherine’s death, William Steffey’s second marriage was to Caroline Baker (1820-1901) in 1843, producing seven more children, including John Steffey. Doctor John Steffey graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1868. He returned to Williamsport, where he practiced “at the residence of his father, on Salisbury Street” until his early death at age forty in 1888.

William Steffey died in 1891, leaving his family with many financial difficulties. A later equity case indicates that Steffey had at least four mortgages on his wife’s mansion. To settle his father’s debts and the estate, William’s son Edward advertised the home for sale in March of 1894 as “a splendid location for a Hotel or Summer Boarding House, terms made easy.” But his stepmother Caroline would not be easily removed from her home; in January 1896, she transferred ownership of the house to her youngest daughter Gertrude Steffey King, wife of the Williamsport postal clerk William H. Z. King.

By 1899, the eighty-year-old Caroline was still living in the house with her daughter and family. Her stepson Edward Steffey had died in March of 1899, and later that year, his widow Elizabeth purchased the home for $50 from her sister-in-law, Gertrude Steffey King. The purchase of the home by Elizabeth Steffey was an act of benevolence, ensuring that her aging stepmother-in-law, Caroline, could remain living in the house she so loved. Caroline died there two years later, in 1901.

After Caroline’s death, Elizabeth Steffey rented out the house, as evidenced by the report of a fire in 1903 on the first floor of the “Steffey property” on Salisbury Street in Williamsport, then occupied by the Robert Myers family. Fortunately, only a Morris chair and rug were destroyed.

In 1908, Elizabeth Steffey deeded the mansion to her recently married son John Grason Steffey “for the natural love and affection.” Grason owned “The Steffey Company,” a Hagerstown coal and building supply business. Grason died in 1931, and his wife Mary remained in the home for another sixteen years. When Mary Steffey sold the grand old mansion in 1945, it had been owned by a member of the Steffey family for over seventy-five years.

Arthur C. and Jesse Temple Fawcett were the new owners of the old mansion. The deed reflects a purchase price of $2,000, yet the newspaper reported the sale price at $8,000. The Morning Herald reported on the sale, noting that the historical residence had nine rooms, spacious halls, and a lovely old stairway. The Fawcetts owned the house for just two years before selling it to John F. and Francis Rodman in 1947.

The Rodmans were initially from Winchester, Va., later moving to Cumberland, where John was the manager of the Eastern Division of the Blue Ridge Transportation Company. The Rodmans were refined, affluent, and socially active. John was the president of the Hagerstown Kiwanas Club and associated with many local civic clubs, garden clubs, and societies. While the Rodmans appreciated the old mansion as a fine antique, they also modernized it by adding several bathrooms and a modern kitchen. Tragically, in 1953, Mrs. Rodman and the next-door neighbor, Doctor Ira Zimmerman, died in an automobile accident near Martinsburg, WV.

The front parlor off the grand entry hall

John Rodman remained in the house until his death in 1961. The Rodman estate sold the home to James Edgar and Lynn Kerwin Byron for $23,200. James “Jamie” Byron was president of W. D. Byron Tannery, the last member of the Byron family to be associated with the tannery until it was acquired in 1975 by Walter Kidde & Co. Inc. His brother was Congressman Goodloe E. Byron. The Byron’s lived in the home from 1961 until 1965, coincidentally, the same years he served as Mayor of Williamsport. When the Byrons offered the house for sale in 1965, a professional brochure extolled the many assets of the old house:

The home has a wide entrance hall running from front to back with a spacious living

room and fireplace, an adjoining formal dining room with sliding wood doors leading to the library, and a full bath with shower, which in addition to the kitchen and utility room, comprise the first floor. Going to the second floor, the lovely wide staircase has a break landing, and on the second floor, you will find five bedrooms, two with fireplaces, and three full baths. There is ample closed closet and storage space. A solarium is located off the stair-break landing, and the house also has a full unfinished attic. In addition, there is a rear stairway to the kitchen from the second floor.

The home has a wide entrance hall running from front to back with a spacious living

room and fireplace, an adjoining formal dining room with sliding wood doors leading to the library, and a full bath with shower, which in addition to the kitchen and utility room, comprise the first floor. Going to the second floor, the lovely wide staircase has a break landing, and on the second floor, you will find five bedrooms, two with fireplaces, and three full baths. There is ample closed closet and storage space. A solarium is located off the stair-break landing, and the house also has a full unfinished attic. In addition, there is a rear stairway to the kitchen from the second floor.

The house has the original wide random-width wood floors, except in the drawing and living rooms. Outside there is a formal garden with an unusually large tulip-magnolia tree, a birch, and several other older old shade trees, flowering shrubbery and vines, six large boxwood, all secluded. . . this house, which we believe to one of the finest of its kind in Western Maryland, is for the discriminating buyer who appreciates the style, detail, and quality of majestic 19th-century houses.

The buyers of the home in 1966 were Robert W. and Grace Cline, owners of Fearnow-Cline, a farming implement business in Hagerstown. The Clines lived in the house for fifty years, and the estate passed to a daughter-in-law in 2016. For several years it was occupied by a caretaker.

By 2021, the old place was beginning to show her age; unattended roof leaks had wreaked havoc with the brickwork and plaster, and the kitchen and bathrooms still sported their 1950s rusting, vintage fixtures. Fortunately, each successive owner had appreciated the house; besides a kitchen and bath, the home retained most of its original detail.

An unusual course of events brought dedicated historians and old house lovers Tom Freeman, an architect, and Ben Tinsley to see the house, which was not on the market. They instantly knew they were looking at something special, recognized the rarity of its “bank-house” history, and determined to own it - which they did in July of 2021.

The formal living room

The historic mansion has undergone extensive restoration since Freeman and Tinsley began in July 2021, including: a new roof on the servants’ wing and carriage house; modern wiring replaced the ancient knob and tube electric lines; original horsehair plaster walls repairs in every room; four full bathrooms updated and re-plumbed; 19th-century crystal chandeliers restored; and original wide-board floors refinished.

Each renovation was carefully thought through to preserve the home’s original details while making it comfortable for modern living. Freeman and Tinsley

also added new features to the house, including a new HVAC system, a new wing to replace the 70-year-old kitchen, and a two-story front porch with a mahogany balustrade reminiscent of the one shown in early photographs of the house.

also added new features to the house, including a new HVAC system, a new wing to replace the 70-year-old kitchen, and a two-story front porch with a mahogany balustrade reminiscent of the one shown in early photographs of the house.

Their elegant collection of antique furniture and art makes the home feel timeless to complete the picture. Restoration continues in earnest with plans for a formal garden.

It is unusual for any house to survive for two hundred years – this home has not only survived but prospered under the loving ownership of each succeeding owner who appreciated its beauty as it quietly matured.

It is unusual for any house to survive for two hundred years – this home has not only survived but prospered under the loving ownership of each succeeding owner who appreciated its beauty as it quietly matured.