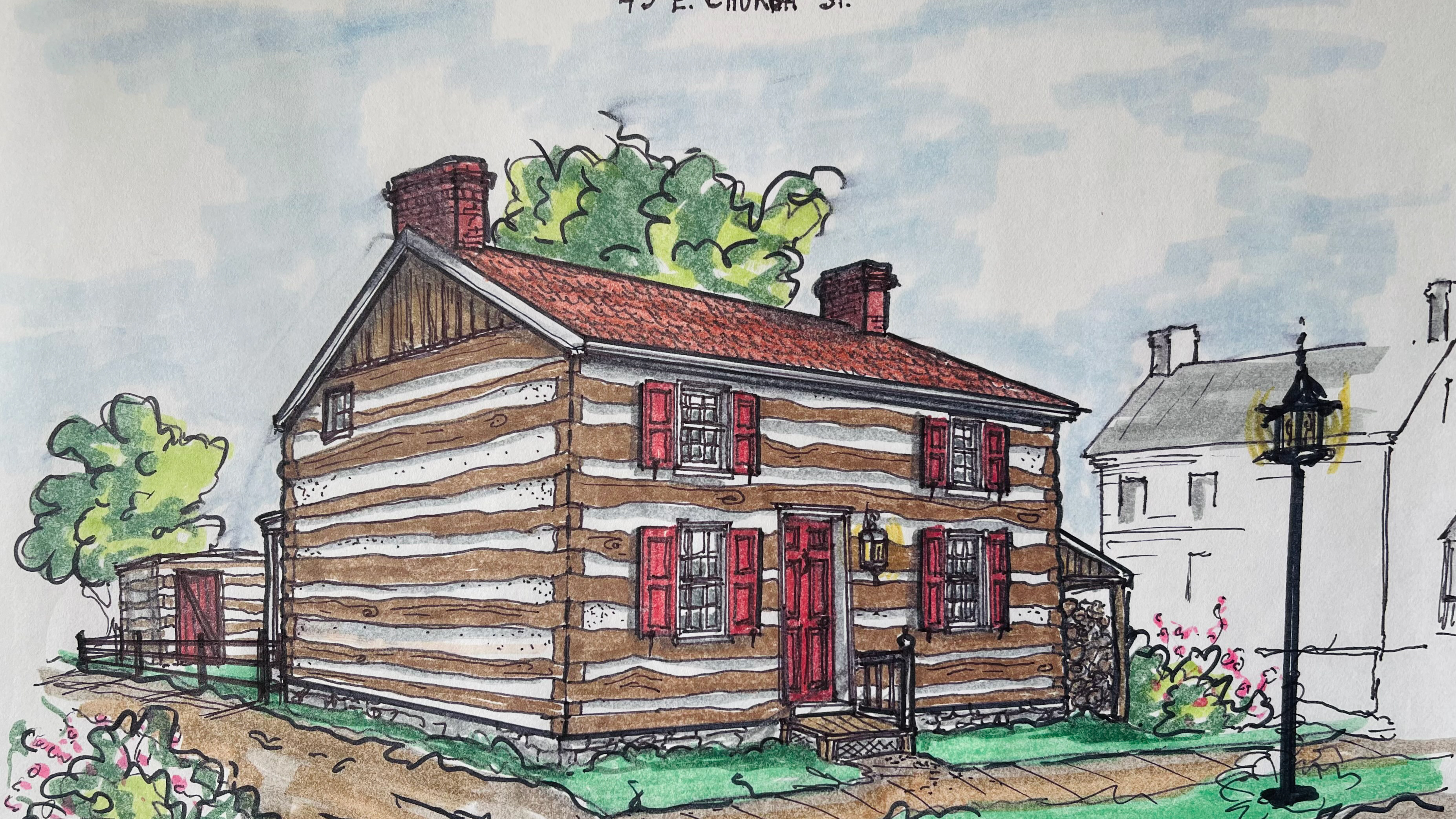

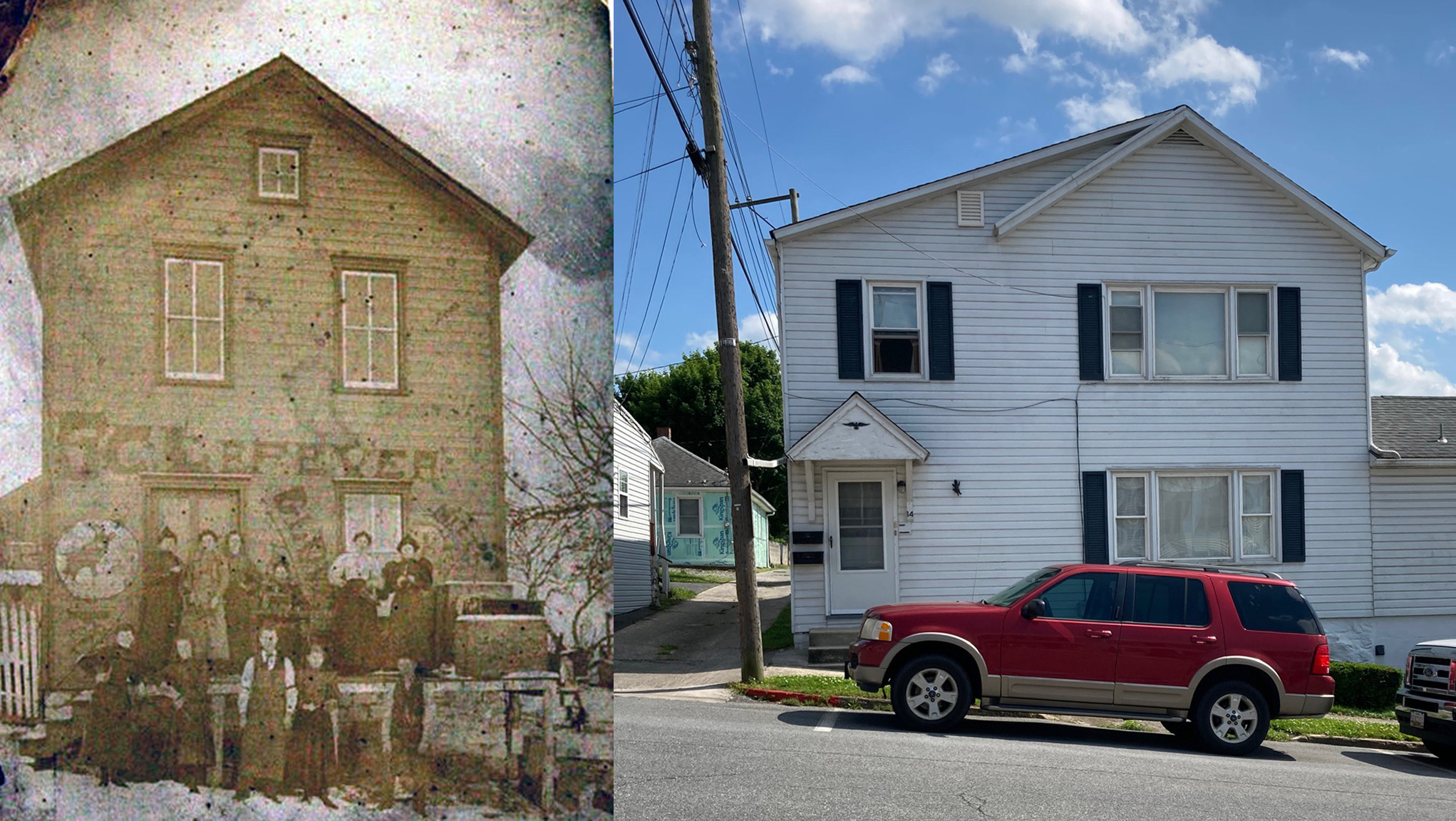

A handsome, early house once stood along the south side of East Church Street, just east of Conococheague Street. The builder constructed this large Federal-style, five-bay, two-and-a-half-story, timber frame house with "brick nogging," a process where the void between the timbers is filled with brick for insulation, then the structure is sheathed with clapboard. An 1807 news article described the home as "forty feet long and twenty-four feet deep, containing a separate stone kitchen, a fine fence, stables," etc. Architecturally, this house was one of Williamsport's finest early homes; historically, it held national significance.

Christian Ardinger leased lot 158 from General Williams in 1788 for the standard terms and was obligated to build a structure on the lot by 1792. Ardinger was born in Pennsylvania in 1745; he was a Revolutionary War Veteran, having served at least five years (see FB post September 21, 2022, The Ardinger House). He and his wife Anna moved to the settlement at the mouth of the Conococheague in 1782, five years before Williamsport was officially established. Christian is buried in Williamsport at River View with an emblem marking his service in the war.

Ardinger must have met his terms modestly as he sold the lot to merchant Thomas Kennedy in 1804 for the low price of $14. The 1804 lease did not stipulate requirements for improvements, proving there was something there. Kennedy subsequently acquired the two adjoining lots, 159 and 160; and by 1805, had enlarged the home to straddled lots 158 and 159.

Thomas Kennedy was born in 1776 in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland. He immigrated to the United States in 1795, settling in Virginia at Great Falls in a now-extinct town called Matildaville. Just across the river in Georgetown, he was employed as an agent for the Potomac Company. By February of 1798, Kennedy was the agent toll collector for the Potomac Company at Williams-Port, and a partner in the commodities firm of John Kennedy & Company, assumed to be his brother. Two years later, the brothers dissolved their partnership, and Kennedy opened a mercantile in a brick house on the Williams-Port public square. In 1802, Kennedy married Rosamond Thomas from Frederick and signed a lease for mill land on the Conococheague.

By 1803, Kennedy had closed his retail store and worked exclusively from his large warehouse on W Potomac Street, lot 223, the original warehouse built by Elie and Otho Holland Williams shortly after the town's founding. From his warehouse known as "The Washington Warehouse," Kennedy purchased or consigned grain, flour, bacon, pork, and whiskey cargoes for transport by his several boats making frequent trips to Georgetown. Additionally, Kennedy stockpiled and sold quantities of pine, oak, poplar, and ash from his sawmill on the Conococheague. A confident merchant and now a family man, Kennedy built his family a fine, large homestead on his three Church Street lots. He also leased lot 134 on W. Frederick Street, where he began constructing a modest house, likely for resale. Today that house still stands at 35 W. Frederick Street.

It is not clear how or why Kennedy's businesses in Williamsport failed. His politely worded notices in the newspaper asking those indebted to him to "please make payment" if they were "able and willing" suggests Kennedy may have been too lenient with others in his financial transactions. In 1805 Kennedy mortgaged his three home lots (158-159-160), the warehouse lot (223), and the unfinished house on W. Frederick Street (134) for the considerable sum of 601£ to William Compton to help settle debts to relatives Joseph and Adiranna Kennedy. Compton gave Kennedy two years to repay the mortgage.

In 1807, William Compton foreclosed and offered all three parcels of the Kennedy real estate in Williamsport at auction. Apologizing for his situation, Kennedy gave notice in the Federal Gazette newspaper of Baltimore that after ten years of industry in Williams-Port, he was quitting his business and vowed to settle every claim someday. Kennedy and his family left Williamsport and moved first to Woburn Manor, then Ellerslie, later Hagerstown, where he lived until his death in 1832.

Thomas Kennedy was an educated, articulate man who enjoyed writing. In 1816 he published a small leather-bound volume called "Poems," a collection of his poetry he began shortly after his 1795 arrival in the United States. He subsequently published "Songs of Liberty and Love" in 1817. After the short but infamous 1823 St. Patrick Day's Irish riot in Funkstown, Kennedy published his satirical poem The Battle of Funks-town. In this lengthy work, the Irish are riotous, drunken "Shamrocks," while the German Funkstown residents are "sons of crouts." The Battle of Funks-town is partly a humorous poem about local events, but a much longer political statement lambasting the educated classes, who Kennedy felt were manipulating politicians for financial gain. In his politics, Kennedy was an anti-Federalist Republican who felt an American aristocracy was emerging from the "business community and eastern elites."

In 1823, Kennedy had reason to strike out. In the vitriolic, anti-Semitic, anti-Kennedy Washington County fall elections of 1823, Kennedy lost his seat in the Maryland House of Representatives, where he had faithfully served since 1817. Kennedy was the author and champion of controversial legislation that would permit Jews to hold political office in Maryland. The Maryland Constitution restricted elected offices to only those of the Christian faith. Kennedy's "Jew Bill," had been introduced and repeatedly defeated from 1819 through 1823. Kennedy would lose the 1823 election, but his efforts would eventually result in the bill's passage in February of 1825.

Probably due to the biased propaganda published about him during the election in the Torch Light and Herald newspapers of Hagerstown, in 1828, Kennedy became the editor of the Hagerstown Mail newspaper. He also served in the Maryland Senate and House until 1831. When a cholera epidemic swept through the country in 1832, many died, including 56-year-old Thomas Kennedy. He and Rosamond rest in Rose Hill Cemetery, Hagerstown. His obituary is a testimony that Kennedy was a kind, caring man, beloved by his community and revered by his colleagues. To this day, Thomas Kennedy is considered a champion of human rights. Acclaimed sculptor Toby Mendez designed and installed his likeness in bronze at the Thomas Kennedy Park in 2017 in downtown Hagerstown.

After Kennedy left Williamsport, Compton sold the leases on the Kennedy home on Church Street to Edmond Turner for the substantial sum of $1,000 in 1807. Edmond H. Turner was born in Maryland in 1778. He first married Rebecca Porter in 1802, and after her death, he married Jane Davis in 1814. The Turners do not appear to have moved into the former Kennedy home. The 1810 Federal census indicates the Turners lived near Fort Frederick.

Edmond Turner died in 1821, leaving his sizeable holdings to Jane. Jane moved to Williamsport and lived in the Church Street house for many years, finally residing in a small house on the western portion of lot 160. In 1839 Jane Turner married Daniel Schnebly. Shortly after the marriage, and likely to protect her dower rights, Daniel and Jane assigned the house on lots 158-159, all the furnishings, including mahogany tables, sideboards, rugs, and silver, and three slaves named Thomas, Rose, and Albert over to John Van Lear, Jr. in a Deed of Trust.

After Daniel Schnebly passed away in 1843, Jane married Samuel Eckles, and the couple moved to Pennsylvania. To alleviate themselves from a debt owed to Doctor Samuel Weisel and others, the Eckles removed the property from the trust with Van Lear and signed the "two-story weather-boarded mansion" over to Weisel, who sold the property to satisfy the Eckles debts.

Williamsport native William Thomas Ensminger (1822-1873) and his young, Clear Spring wife Elizabeth [Little] (1836-1910) purchased lot 159 and half the house, and his brother Merideth Ensminger (1826-1904) and wife Mary Ann bought lot 158 and the other half of the house in 1853 for $375 each. The brothers divided the house into two separate living quarters. Meredith and Mary Ann later improved their half by adding the two-story addition to the home on the western side.

During the Civil War, the old mansion on Church Street once again gained recognition. In the fall of 1861, Company I and K of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry received orders to vacate Harper's Ferry and move to winter quarters at Williamsport to defend the canal from marauding Confederates. Marching and boating up the Potomac River, they carried a "trophy of war" - the bronze bell removed from the engine house at the Federal Armory. The same engine house where Abolitionist John Brown made his last stand during his infamous raid to free the slaves in October 1859. The building was known as "John Brown's Fort," and this was the "John Brown" Bell.

The soldiers stated they received orders to seize anything of value to the US government lest it fall into the hands of Lee's Confederate Army. Coincidentally, several Company "I" members were firefighters who thought the bell would make a fine addition to their hometown engine house in Marlboro, Massachusetts. They just needed to devise a plan to transport the 700-800 pound bronze bell almost 500 miles to the north.

Williamsport was truly a town with divided sentiments during the Civil War. At the Luthern Church, the pastor resigned, declaring he could not serve a congregation so divided. Townspeople had mixed reactions to the occupation by the 13th Massachusetts; young Lydia Corby spat and cursed the soldiers at every opportunity, while Constable William Ensminger and his wife Elizabeth saw great value in soldiers defending the town's livelihood on the canal. They befriended the soldiers, and Elizabeth was engaged to provide fresh-baked bread to the soldiers.

Early in 1862, part of Massachusetts infantry was ordered first to Hancock, Md., then south to Winchester, Va., in pursuit of Stonewall Jackson. Knowing they couldn't drag their trophy on a campaign, they entrusted the bell to Mrs. Ensminger.

In September of 1892, six members of Company "I" 13th Massachusetts veterans traveled to the 26th National GAR Encampment in Washington, DC. On their way home, they stopped at Williamsport, where they had camped thirty-one years previous. Reportedly, the Union veterans were refused accommodations at the local hotel, so they looked up their old friends, the Ensmingers, on Church Street. William Ensminger had died in 1873, and Elizabeth, still a young woman, had remarried boatman George Snyder. Image the veteran's surprise to see their trophy bell standing on a post in the Snyder's backyard, Elizabeth having buried the bell during the war years for safekeeping.

The veterans returned to Marlborough and raised the money to transport the bell north. It now hangs in a specially constructed tower in the Union Commons Park. In recent years, the National Park Service and the town of Harper's Ferry have tried in vain to convince Marlborough to return the bell and place it on the reconstructed engine house. Marlborough is proud of the bell, declaring it second only to the Liberty Bell in national importance.

The old mansion on Church Street stayed in the Ensminger/Snyder family until 1929 when purchased by the Lumm family. Eventually, the Calvary Temple Church bought the lots and house in 1961. For decades the church used the house for numerous purposes. The house was placed on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Places in the 1970s and listed as a contributing structure in Williamsport's National Register of Historic Places nomination in 2001

Inexplicably, in 2018, the church decided the historic home with its lovely hedge and witness tree had no value, and a larger parking lot was more beneficial. Regardless that a curbside historic placard identified the house as an important historic structure, the town of Williamsport rubber-stamped an approval for demolition. There was no public notice, no opportunity for public input, and no advance warning in the summer of 2018 when a demolition crew arrived with the backhoes. The neighborhood watched in shock and anger as the crew demolished one of Williamsport's treasures into rubble, burying its historic timbers into its foundation.

Demolition photos courtesy Debra Carbaugh Robinson

Williamsport boasts of its rich history, deep family roots, and optimization for the future. Yet, it still needs to take the steps that would, if not prevent, definitely slow, unwarranted demolition or tragic modification. It should be mandatory for demolition or significant alteration applications of any town building listed on the National and State Historic Register to be subject to review by a Williamsport Historic District Commission and the Town Council (which currently holds this responsibility yet disregards it.) When all our history has is shoveled into a hole in the ground, and nothing is left but memories, what happens to Williamsport? I ask you, citizens of our beloved town, what do you want our future to look like?

Williamsport's brick, stone, and wood history is valuable and essential to our future and should be protected.