Near the bottom of town hill at 153 N. Conococheague Street sits a vacant lot backing up to the locally famous Springfield Run waterfall that plunges toward Conococheague Creek. Until 2009 an ancient stone house shrouded in mystery sat quietly against the rushing stream, far back from the road. The house's architecture was unusual, bearing no resemblance to other surrounding buildings. This house was constructed from rough-cut limestone and built directly into the rock hillside. The right side of the house was 2 1/2 stories tall, the left 3 1/2 stories tall, with a workroom accessed by a door in the ground-level facade — the windows and doors were supported by simple wooden lintels. The stone walls were nearly two feet thick, with plaster applied directly to the stone on the interior. Simple original woodwork trimmed the doors and windows with a utilitarian good-morning staircase that rose to the second floor from the hallway. The house had several fireplaces and wide board floors of heart pine.

This house has been a mystery for as long as anyone can remember. When was it built? By who? Was it a commercial building, or was it a residence? Because the house sat on a small parcel of land immediately adjacent to, but not part of, the original 1787 town of Williams-Port as laid out by Otho H. Williams, the deed trail was challenging to research.

Further complicating the deed trail, this property was part of several late 19th and early 20th-century "Additions" to Williamsport by Victor Cushwa in the 1870s-1910. Williamsport was considered second only to Hagerstown for economic importance and growth in Washington County during those years. So, where does this leave us today? The deed trail notes the land was originally part of three land parcels: Swede's Delight, Dear Bargain, and Manor Reserve #7.

As early as 1732, Charles Friend lived on the Potomac River at the mouth of the Conocheague Creek. In 1739, he received a patent for "Swede's Delight," about 260 acres bordering the Potomac River and the Conococheague Creek. Two years later, Friend received a second patent for a narrow sliver of 25 acres bordering Swede's Delight on the east and bounding both sides of the Conococheague Creek. The patent includes an unusual affidavit signed by Colonel Thomas Cresap relinquishing his claim to these 25 acres, noting that this was initially land he had claimed. The conflict between Friend and Cresap for the 25 acres bounding the Conococheague must have been costly, as Friend named his land "Dear Bargain." Swede's Delight and Dear Bargain remained in the Friend family until the early 1800s. Thomas Cresap, Charles Friend, and later Otho Holland Williams understood the economic importance of controlling the waterway and "mouth of the Conococheague." Just north along the Conococheague Creek once stood a massive stone mill known as Ardinger's Mill, also dating to the latter part of the 18th century.

Colonel Jacob Wolfe (1744-1835) was a hero of the Revolutionary War and the first elected Mayor of Williamsport from 1824 until 1830. In 1808, Colonel Wolfe paid £60 for the 1.14 acres where this stone house once stood. Sixty pounds was a considerable sum for just one acre, proving that the Friend family had made substantial improvements on the small parcel, likely including a stone tannery.

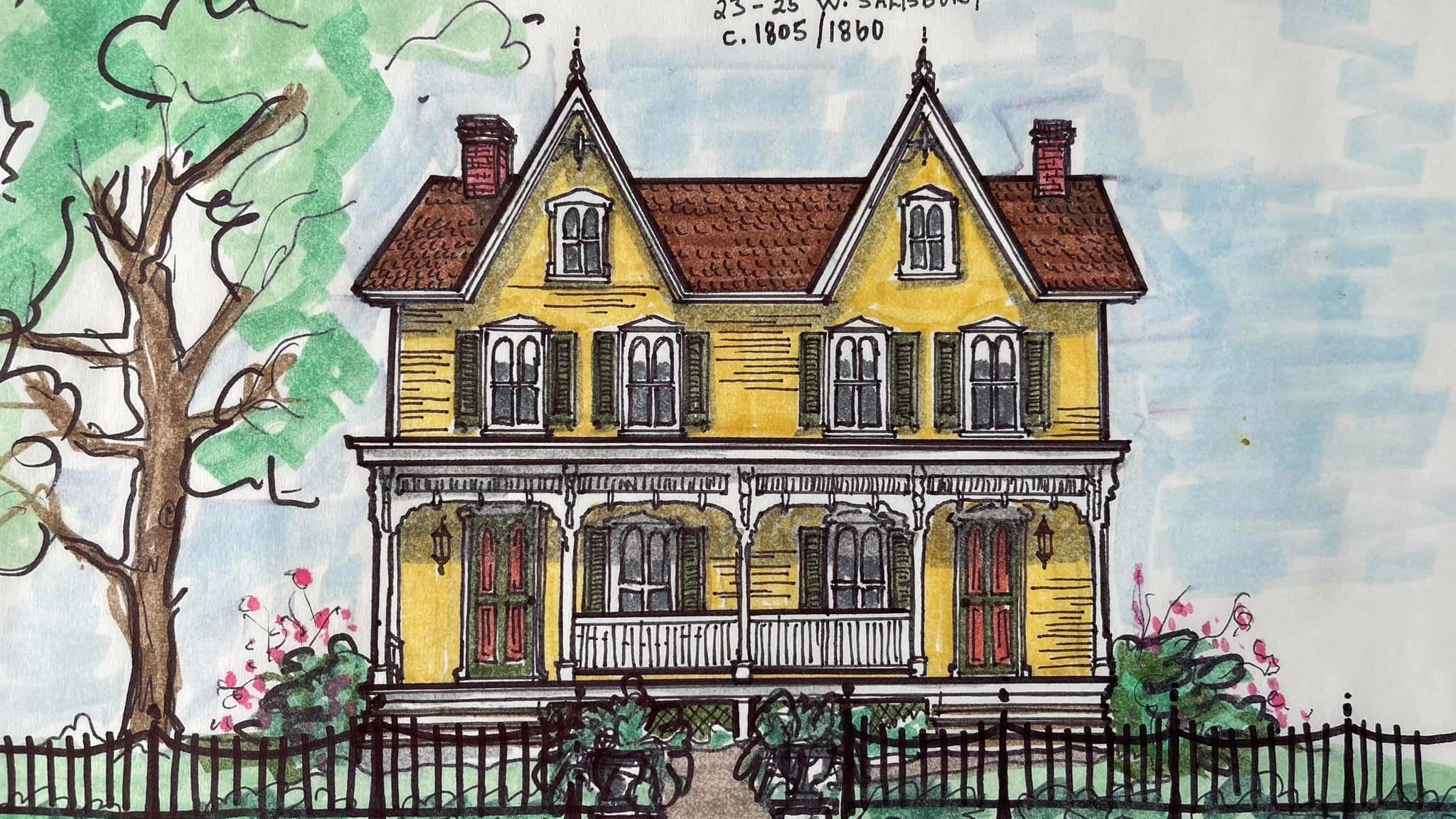

The heirs of Jacob Wolfe sold the stone tannery to Henry and Samuel LeFever in 1842. The LeFever family had several businesses in town. More about them can be found in our post about the LeFever House (now restored) from June 28th.

The heirs of Jacob Wolfe sold the stone tannery to Henry and Samuel LeFever in 1842. The LeFever family had several businesses in town. More about them can be found in our post about the LeFever House (now restored) from June 28th.

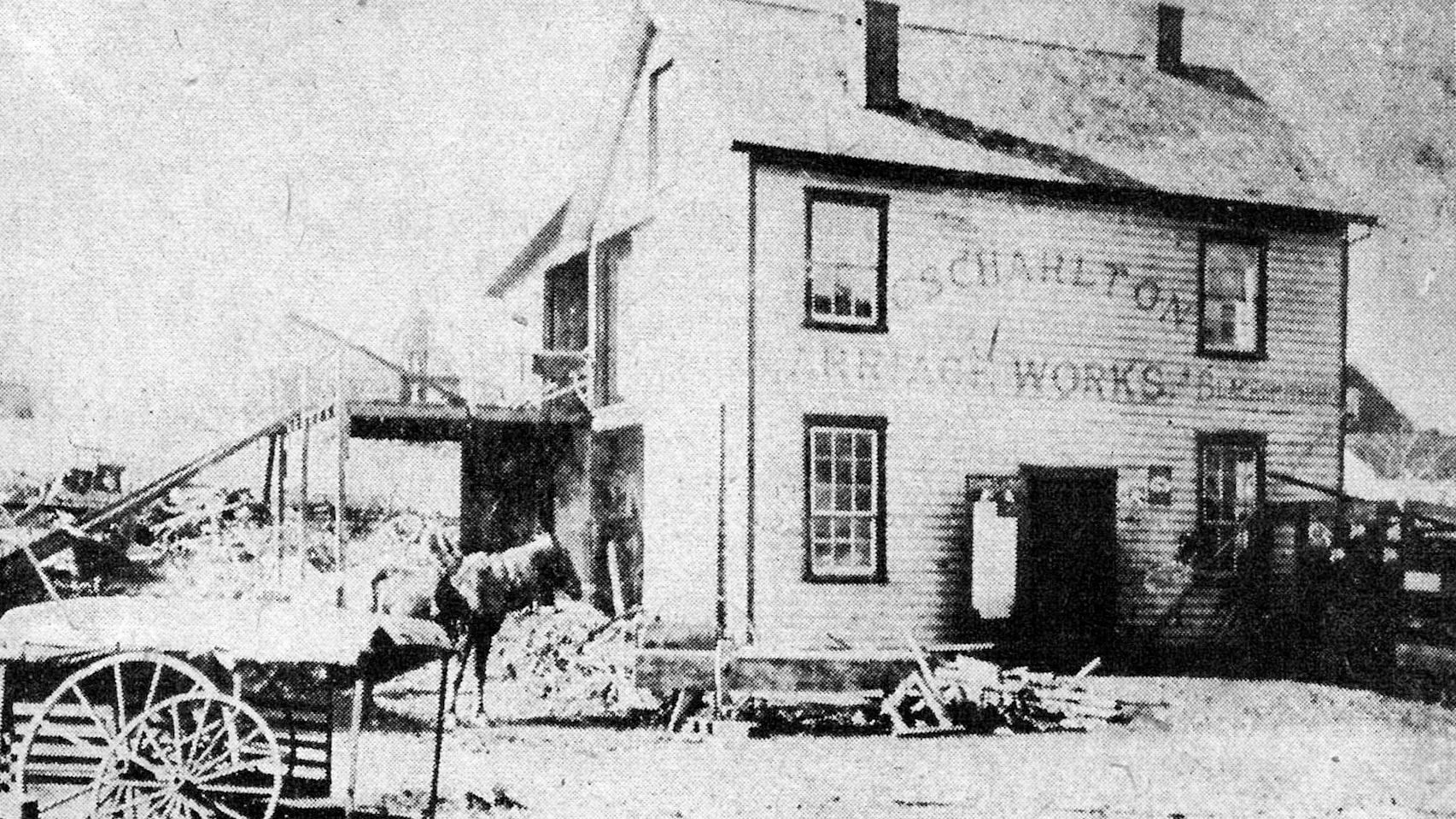

Victor Cushwa purchased the tannery from the Lefever heirs, and then bought most of the land on the east side of the Conococheague Creek. He built "Cushwa Avenue" connecting Artizan Street to N. Conococheague Street behind his home at 37-39 E. Potomac Street as a shortcut to his brickworks. In 1866, Cushwa sold 1.14 acres of the parcel "on which is erected a tannery and other buildings" for the whopping sum of $3,500 to William H. Schildneck.

The Schildneck family of Middletown Valley owned several tanneries in Frederick County and had recently expanded their operations into Hagerstown. In his 1910 book, "Middletown Valley in Song and Story," T. C. Harbaugh described Schildnecks tannery near Myersville as ". . .a long, rambling two-story structure. The basement contained the vat room, bark shed, engine room, etc., and went out level with the back yard, in which there were also vats. The second story came out level with Canaan Road and was the storage and finishing department. The place was rather spooky after dark, and timid people frequently gave it a wide berth." A description that closely resembled the stone tannery at Williamsport. In addition to the purchase price, the Schildnecks paid Cushwa an additional $200 for the right to run a two-inch pipe about 25 feet across Cushwa's land to direct spring water into the tannery.

Later that year, William H. Schildneck sold the tannery to his sons Vandyke and Lawson Schildneck. He also sold them tools, equipment, and hides from the Schildneck Tannery in Hagerstown. Heavily mortgaged, the Schildneck brothers were less successful than their father, and by 1870, they declared bankruptcy and sold the property back to Victor Cushwa for $500.

The Forsythe Family purchased the stone tannery in the early 20th century and transformed it into a rental home. During and after prohibition, George and Arlene Strain industriously erected a still on the property and supplied thirsty travelers at the nearby railroad train station. Sadly, the Strains were put out of business by the destructive flood of 1936 when the water level rose above the house's second story and destroyed the still. Several families, including the Shipley Family, rented the home over the following decades.

The Myers family were the last owners of the old stone house, purchasing it in the 1980s. Family members described a rock and concrete wall with remnants of a waterwheel fed from the rushing water of Springfield Run at the back of the old house. The wheel terminated in the lower level of the house where there was a large "workroom," long stripped of whatever tannery mechanisms and vats it once housed. Jimmy Myers still speaks of window sills so deep that he could hide inside them while playing hide and seek with his siblings.

Now, at over 200 years old, the old home was in serious need of repair after decades of hard use and numerous floods. The Myers family had just begun renovations when tragedy struck in 2009. A damaged chimney allowed embers to escape into the attic igniting the old cedar shake shingles; in a short time, the home was engulfed in flames. The family escaped without injury but lost most of their possessions. Some consideration was given to restoring the house as the massive stone walls still stood, but it was ultimately rejected. Shortly afterward, the 220-year-old house was demolished. Sadly instead of restoration, repurposing, or adaptive reuse, the old place fell victim to a short-sighted "easy fix."

Many Thanks to the Williamsport Area Historical Association, the Myers Family, and the citizens of Williamsport for all of their help with this post.

As we close 2022 and begin a new year, please reflect on the nearly 30 stories of lost and preserved historic buildings that have been profiled since April. Williamsport is an important historic place and this place matters. Our structures tell our story long after we are gone and should be respected. Thank you to all the people who work hard to make this a great place to live, those who support historic preservation, and are investing in our community. There is still more to be done, and I hope 2023 brings Williamsport prosperity and continued energy to keep up the good work. Happy New Year!