Original watercolor rendition of the Williams Log House 19-21 W Salisbury by Tom Freeman

Porter made no improvements on his relinquished lots as he released three of them back for just $20.

Photo of the Williams house 1978 before demolition

Otho Holland Williams by Charles Willson Peale, the original is displayed at the Society of Cincinnati, Washington DC

Elie Williams by Charles Willson Peale. The original is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

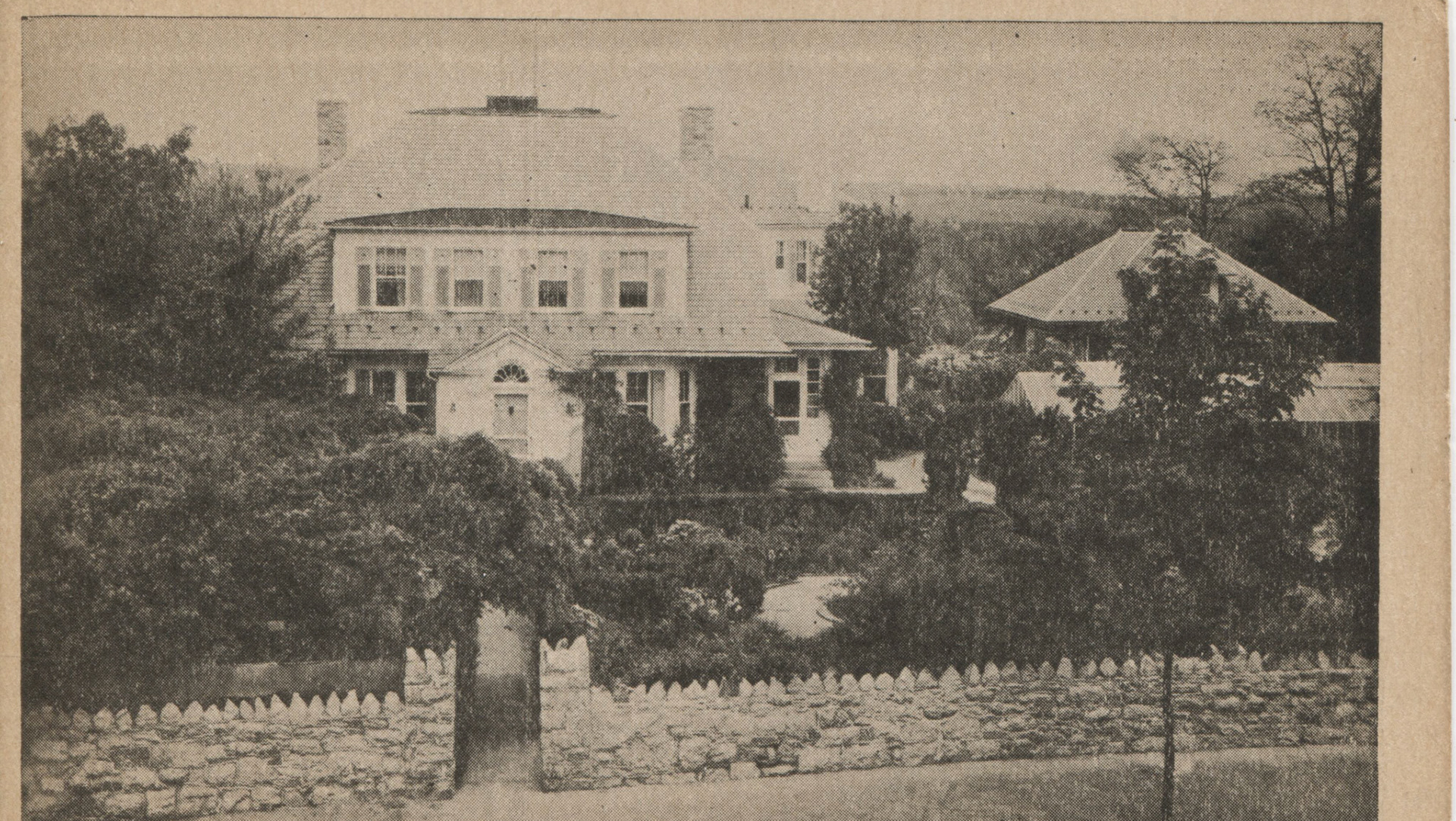

The house in the 1930s. Photo by WPA

Location of the home of Otho Holland Williams home in the late 18th century

An elegant 18th-century Baltimore townhouse comparable to the Williams home

Mary Smith Williams White (1822-1907). Daughter and heir of General Edward Greene Williams and granddaughter of General Otho Holland Williams. At age seven, Mary inherited almost the entirety of Williamsport.